[ad_1]

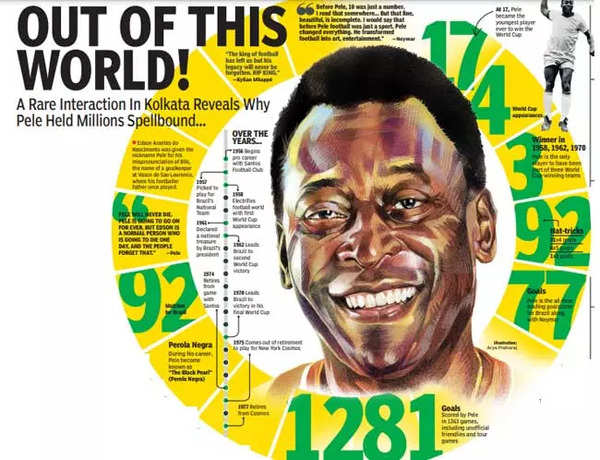

For someone who was among the most-photographed personalities of the last century, alongside the Beatles, Elvis, Monroe, Loren and Ali, this was perhaps a never-before capture, even for Pele. The image is yet another example of what a fine specimen of an athlete Pele was. The near-perfect musculature lend him a ready handsome-ness, beauty in power. Till date there isn’t a footballer, or any athlete in any sport, as physically perfect as Pele was.

Yet what sets the image apart, making it special, is the idea of thrusting a book in Pele’s hands. It makes him transcend from a legendary, genius footballer to something of a cultural treasure. Pele was never known to be a man of letters, and it may have been an accounting journal for all we know. However, the composition symbolises the idea of how football is – or once was – deeply connected to the literature and arts of Brazil.

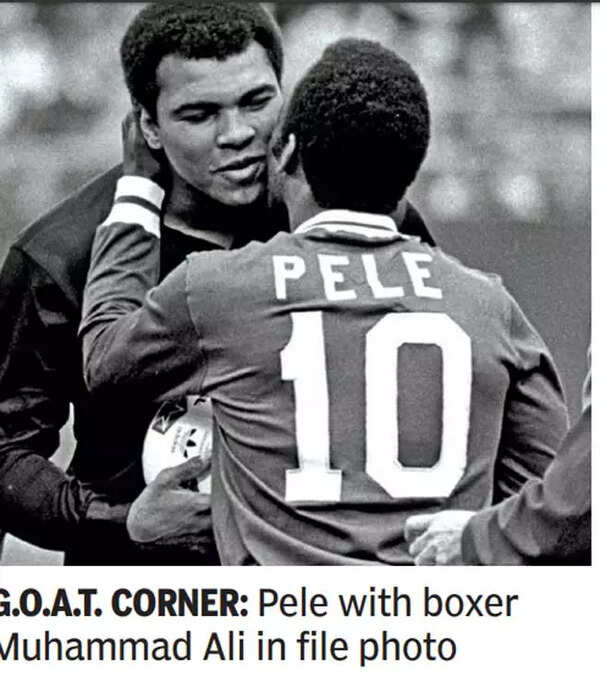

Brazil would famously anoint Pele as a national treasure, preventing the top clubs of Europe from poaching him. He would still go on to become the most recognisable faces of the 21st century as film became more accessible and photographs and flickering newsreels became the documents of history. You could argue that Mohammed Ali earned global love with his charisma and for his stand on race in the latter part of his career. Pele was doing it in his prime, without speaking English and with the ball at his feet. He was becoming the most famous face of all time, and as we would realise later, the first-ever global sports hero.

Pele, the legend who wowed the world, dies

Of course, the worldwide colour telecast of the 1970 World Cup and later, a push by Warner Brothers and NY Cosmos did help. What is staggering is that in a world yet to be overrun by PR machinery, he had managed the feat completely from South America alone. That’s quite an achievement when you consider how stranded Latin American pop culture is today, when even a callow Mbappe can confidently dismiss their football as backward compared to Europe’s.

Almost all workers in a Brazilian automobile assembly plant were famously able to name Pele when they were shown his photograph. Kidnappers once bolted, apologising when they learnt who they had abducted. Pele has, briefly, even stopped wars in Africa. Then we all knew that the world had changed when, in 2008, Pele was robbed at gunpoint by a gang of young men even after he told them his name.

Till then, it had helped that his name would carry its own instinctive recall – Gulzar would so simply slip it in the verses for his cult film ‘Gol Maal’, where Pele would even figure as a question during a job interview.

Even in John Houston’s ‘Escape to Victory,’ he was Pele, even though he played Corporal Luis Fernandez. That bicycle kick goal for Allieds against the might of the Nazi Germans became imprinted in our minds.

Even if we didn’t really see him play, Pele would still come to us as comprehension passages in our internal exams at school, as chapters in high school syllabi. School libraries would invariably have a dog-eared comic-book-form biography of the football god. On playgrounds, we would fight to own the No. 10 jersey even if we were playing hockey.

Pele was a permanent fixture of sorts, a four-letter word that was not taboo, much before private sports channels and YouTube became the norm. Somehow, paradoxically, once that happened, the explosion of 24-hour sports television invaded our senses and humanised the man for us.

[ad_2]

Source link