[ad_1]

CNN

—

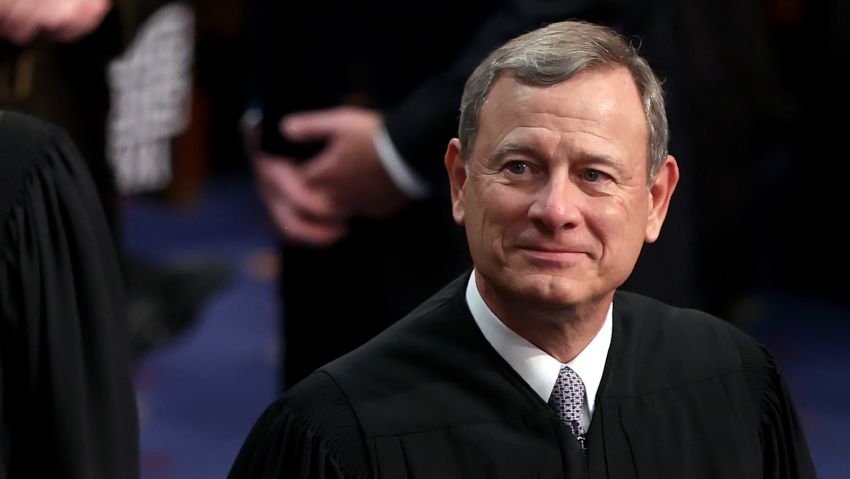

After more than three hours of oral arguments in a single case last week, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts uttered the traditional closer, “The case is submitted.”

But the hearing wasn’t over. Roberts, a details man who usually hews to script, had forgotten that a lawyer had yet to take his rebuttal time.

“I’m sorry,” Roberts said to Matthew McGill, who rose to his place at the lectern. “It is late.”

Yet another Supreme Court case had gone nearly twice as long as scheduled – a pattern testing the nerves of the justices this fall. Some exchange glances when a loquacious colleague engages in protracted questioning. Many interrupt answers to queries simply to get their own in. Roberts, in the center chair and keeping track of the interjections from the left and right, often looks weary, leaning head on hand.

The usual morning sessions that begin at 10 a.m. are going well past the noon lunch hour. When the court heard a pair of challenges to the use of affirmative action in college admissions on October 31, the justices went without lunch until after 3 p.m.

Still, as much as the marathon arguments have challenged the stamina of everyone in the courtroom, they have provided early insights on the justices this 2022-23 term.

Liberals, who lost ground on many areas of the law last session, notably when the conservative majority jettisoned women’s abortion rights, have come back strong in the court’s most public forum. Those three on the left (Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson) have actively tried to poke holes in cases but also have been making sweeping statements to draw attention to larger liberal concerns.

“I think Kafka would have loved this,” Kagan declared of a state system that repeatedly thwarted a murder defendant’s challenge to his death sentence.

John Roberts skewers Harvard attorney’s comparison of race and music skills as qualities in applicants

02:00

– Source:

CNN

The two most consistent conservatives, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, have demonstrated how much further to the right they want to push the court to narrow federal voting safeguards and eliminate college affirmative action. They appear ready to reverse a 1978 landmark decision that allowed race-based admissions to enhance campus diversity.

“I’ve heard the word ‘diversity’ quite a few times,” Thomas said, “and I don’t have a clue what it means. It seems to mean everything for everyone.” Thomas has criticized affirmative action as unconstitutional as well as stigmatizing to Black students.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, who is usually with Thomas and Alito on cases, reinforced in recent arguments where he parts company. The court’s most prominent supporter of Native American rights, Gorsuch staunchly defended the Indian Child Welfare Act’s preferences for placement of Native American adoptees with other Native American families.

A key question is whether the law unconstitutionally discriminates on the basis of race or allows the federal government to tread on state authority. “I’m struggling to understand why this (law) falls on the other side of the line, when Congress makes the judgment that this is essential to Indian self-preservation of Indian tribes,” Gorsuch said.

Fellow conservative Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett are known to offer mixed signals in the public oral argument sessions. They sometimes suggest a middle-ground course but then move right when it comes time for the bottom-line vote.

Roberts is still largely with his fellow conservative appointees, although he has joined the left in a few high-profile instances. So far this session, he has rarely dominated the hearings, but he has pressed his own interests, especially to end race-based practices. And in the Indian Child Welfare Act dispute, he expressed concern that the law would cause the best interests of the child to “be subordinated to the interests of the tribe.”

Until the Covid-19 pandemic, beginning in early 2020, Roberts presided over fairly tight one-hour sessions. As justices jockeyed to ask questions of a lawyer standing below the bench, speed and brevity were valued. The clock ruled, and rarely would a case get more than one hour of time.

When the justices moved to teleconference questioning during the pandemic, Roberts necessarily changed the routine so that the attorneys at the other end of the phone line knew which justice was speaking. Each of the nine justices was to take about three minutes to ask questions, in order of seniority.

Many of them went over time, as did the lawyers at the other end of the phone line. But the format had the advantage of ensuring that no justice was elbowed out of the Q-and-A.

Since returning to the courtroom late last year, the justices have employed a format that begins largely with the old free-for-all but then adds a second round during which each justice gets a chance to ask any lingering queries.

That has encouraged talkativeness – especially of the newest justice, Jackson. Adam Feldman, who tracks patterns during oral arguments at his Empirical SCOTUS blog, found that during the first two weeks of cases argued in October Jackson spoke more than twice as much as any other justice, based simply on word count.

The justices’ actual votes in cases occur behind closed doors and the outcomes of the biggest controversies are unlikely to emerge until next spring. Still, argument by argument, one by one, the justices are revealing dimensions of themselves now.

Listen to Ketanji Brown Jackson school the Court on US history

02:32

– Source:

CNN

Roberts, 67, appointed by President George W. Bush in 2005

In trying to keep order in the give-and-take and move things along, Roberts has gotten ahead of himself more than once.

During an October argument he presumed the justices’ questioning of lawyer Timothy Bishop in a dispute over a California law regulating pork sold in the state, tied to the confinement conditions for pigs in other states, was finally over. So he called up the next lawyer, deputy US Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler.

But Bishop wasn’t moving away from the microphone. Bishop was still entitled to the second round of justices’ questions. Sotomayor said hesitantly, “Chief?” That’s when Roberts realized his mistake. “Oh, I’m sorry, Mr. Kneedler,” Roberts said, indicating that he should stay seated, and turning to his colleagues for questions to Bishop.

On the substance of the early cases this session, Roberts has revealed his continued abhorrence for race-based classifications. Echoing some of Thomas’ criticism for admissions practices at the University of North Carolina, Roberts told state solicitor general Ryan Park, “Your position is that race matters because it’s necessary for diversity, which is necessary for the sort of education you want. It’s not going to stop mattering at some particular point. You’re always going to have to look at race because you say race matters to give us the necessary diversity.”

Thomas, 74, a 1991 appointee of President George H.W. Bush

The current court’s longest-tenured justice rarely spoke under the old pre-pandemic format, turned off by the rapid-fire questioning. In the modified format, Roberts gives Thomas the first question of the first round, before other justices engage, and then returns to him as the structured second series begins. Thomas makes points on the law and has shown some levity.

In a copyright dispute involving a Lynn Goldsmith photograph of the musician Prince adapted in an illustration by Andy Warhol, Thomas began a hypothetical query, “… let’s say that I’m both a Prince fan, which I was in the ’80s and …” Before he could go further, Kagan interjected, “No longer?” To laughter, Thomas responded, “Well… so only on Thursday nights.”

Then he continued: “But let’s say that I’m also a Syracuse fan, and I decide to make one of those big blowup posters of Orange Prince and change the colors a little bit around the edges and put ‘Go Orange’ underneath. Would you sue me for infringement?”

Breyer discusses the division on the Supreme Court

Alito, 72, a 2006 appointee of George W. Bush

He has always been a sharp interlocutor who does not hedge his views. In a voting rights case from Alabama, he made plain that he would narrow the reach of the Voting Rights Act in a way that would make it harder to prove race discrimination in voting practices, such as redistricting. (Alabama’s Black population is about 27%, but only one of its seven congressional districts has a Black majority, and a lower federal court found that the map diluted Black votes in violation of the VRA.)

Alito suggested the approach of challengers to the Alabama map would set an easy standard that allows them to “run the table” against a state. He also suggested that “a community of interest,” involving residents’ common backgrounds supporting a second Black-majority district, was an invalid “proxy for race.”

Separately, Alito has also implied he may feel a bit over the hill. He drew some courtroom laughter in one case when he referred to a 1974 law and quipped, “I actually do remember 1974.” In another, regarding overtime pay and time-off practices for executive and daily wage workers, he said, “Does somebody who’s out working on an oil rig have the option, as a practical matter, to take the day off? I’d like to take the day off and play golf.”

Sotomayor, 68, a 2009 appointee of President Barack Obama

After Thomas laid out his scenario regarding copyright of a photograph of the late musician Prince, Sotomayor began her round of questioning lightly, “I think my colleague, Justice Thomas, needs a lawyer, and I’m going to provide it.”

Sotomayor, who is now the court’s senior liberal, is also a sharp questioner, admonishing evasive lawyers and directly countering colleagues. Regarding Alito’s comments on voting rights, she said, “Justice Alito gave the game away when he said race-neutral means don’t look at community of interest because it’s a proxy for race.”

And she said his approach to the 1965 Voting Rights Act would essentially turn the law “on its head.” The country’s first Hispanic justice, Sotomayor stressed that the law was intended to ensure that “a particular racial minority … can equally participate.”

Kagan, 62, a 2010 appointee of Obama

She often relies on a colloquial style to make her legal points, contrasting in the affirmative-action dispute, for example, “White men (who) get the thumb on the scale” with “people who have been kicked in the teeth by our society for centuries.”

But she often voices larger dilemmas of the country’s law. In the controversy over federal safeguards for election practices, Kagan described the 1965 Voting Rights Act as “one of the great achievements of American democracy, to achieve equal political opportunities regardless of race, to ensure that African Americans could have as much political power as White Americans could. That’s a pretty big deal.”

During an Arizona capital case, she rebuked a deputy state attorney general for flouting earlier Supreme Court decisions requiring jurors to be told in certain cases if the murder defendant would be ineligible for parole if sentenced to life.

“It suggests that the state in its many forms, many actors, is just insisting on not applying (precedent)…,” Kagan said. “It sounds like you’re thumbing your nose at us.”

Justice Kagan speaks out on SCOTUS’ record-low favorability

Gorsuch, 55, a 2017 appointee of President Donald Trump

In oral arguments, he is variable. He did not ask a single question during the nearly three hours of arguments on the Voting Rights Act. But he dominated the dispute over the placement of Native American children in foster or adoptive care.

The 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act sets out preferences for Indian children placed in foster care or adopted: the child’s extended family, other members of the Indian child’s tribe, and other Indian families, over placement with a White or other non-Native American family.

When he addressed Texas solicitor general Judd Stone, who was urging the court to strike down the law as discriminatory and an overreach of Congress’ power, Gorsuch said, “how about the fact that the federal government has been heavily involved in domestic affairs, with respect to Native American children throughout our history, whether it’s through treaties, orphan children, or whether it was through the boarding school saga of the last century?”

Gorsuch questioned why that pattern wasn’t evidence of Congress’s nearly unlimited power in this area of the law. When Stone said Congress might have been invoking its “ordinary powers” involving territory or appropriations, Gorsuch shot back: “They took children off-reservation, counsel.”

Kavanaugh, 57, a 2018 appointee of Trump

He regularly speaks of balancing interests. In the Native American adoption case, he said, “The equal protection issue is difficult, I think, because we have to find the line between two fundamental and critical constitutional values. So, on the one hand, the great respect for tribal self-government for the success of Indian tribes … with recognition of the history of oppression and discrimination against tribes and people. … On the other hand, the fundamental principle we don’t treat people differently on account of their race or ethnicity or ancestry, equal justice under law…”

Kavanaugh sits between Jackson and Kagan at one end of the bench and can sometimes recede as they pummel the lawyers before them.

At one point in an employee compensation case, he and Jackson were simultaneously asking questions. Flustered, the lawyer said, “This is my first argument. Now I got two … I don’t know how to go….” Suggested Kavanaugh, “Answer them both.”

Barrett, 50, appointed in 2020 by Trump

She sits at the far other end of the bench, and appears mindful of the time, looking down the row to make sure she’s not about to cut off a more senior colleague’s question.

Her queries and hypothetical scenarios often reflect her background. “I grew up in New Orleans. The whole thing is below sea level,” she said during a controversy involving Clean Water Act regulations that limit building construction. “So, you know, there are aquifers that run right underneath it. We have no basements because, you dig far enough in anybody’s yard, you hit water, and all of that runs into Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River, navigable waters.” She wondered, therefore, whether anyone who wanted to build on a lot would have to obtain a Clean Water Act permit before proceeding.

Her inclinations related to social policy dilemmas emerge, too. In the dispute over California regulation of pig confinement to prevent animal cruelty, she asked, “So, could you have California pass a law that said we’re not going to buy any pork from companies that don’t require all their employees to be vaccinated or from corporations that don’t fund gender-affirming surgery or that sort of thing?”

Judge Jackson in remarks: I am the dream of the slave

Jackson, 52, appointed this year by President Joe Biden

The former federal public defender and first Black woman justice has tried to pull the court leftward on criminal defense and racial issues.

During the case involving Alabama’s voting map and the challengers’ effort to obtain two Black-majority districts, Jackson said, “I don’t think we can assume that just because race is taken into account that that necessarily creates an equal protection problem, because I understood that we looked at the history and traditions of the Constitution, at what the framers and the founders thought about. … When I drilled down to that level of analysis, it became clear to me that the framers themselves adopted the equal protection clause … in a race conscious way.”

In the second month of arguments, Jackson has seemed slightly more attentive to the time she is consuming. “I have little time,” she told one lawyer as she cut off his answer to her so she could get another question in. In a separate criminal case, as a government lawyer was finishing his opening statement, she immediately began asking a question.

But then she caught herself. “Sorry,” she said, looking down the row, “Does anybody else have a question?” Hearing nothing, she fired off a series of queries.

Source link