[ad_1]

Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

Beijing

CNN

—

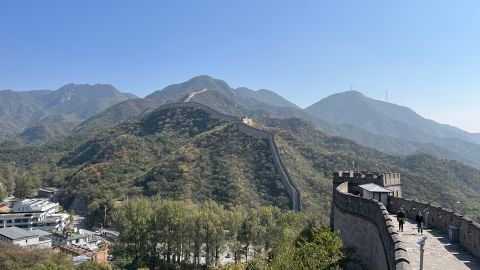

During China’s ‘National Day’ holiday in early October, several expatriate friends and I took our young children – who are of mixed races and tend to stand out in a Chinese crowd – to the Great Wall on the outskirts of Beijing.

As we climbed a restored but almost deserted section of the ancient landmark, a few local families on their way down walked past us. Noticing our kids, one of their children exclaimed: “Wow foreigners! With Covid? Let’s get away from them…” The adults remained quiet as the group quickened their paces.

That moment has lingered on my mind. It feels like a snapshot that illustrates how China has changed since its strongman leader Xi Jinping took power a decade ago – it’s become an increasingly walled-in nation physically and psychologically – and such transformation will have long-term global implications.

Understanding the big picture is timely as Xi is poised to break convention to assume a third term as the head of the Chinese Communist Party – the real source of his power instead of the ceremonial presidency – at the ruling party’s twice-a-decade national congress, which opened in Beijing on Sunday.

The Great Wall, a top tourist attraction that normally draws throngs of visitors during holidays, stood nearly empty when we went thanks to Xi’s insistence – three years into the global pandemic – on a policy of zero tolerance for Covid infections while the rest of the world has mostly moved on and re-opened.

China’s borders have remained shut for most international travelers since March 2020, while many foreigners who once called the country home have chosen to leave.

With the highly contagious Omicron variant raging through parts of the country, authorities had discouraged domestic travel ahead of National Day holiday. They are also sticking to a playbook of strict quarantine, incessant mass testing and invasive contact tracing – often locking down entire cities of millions over a handful of cases.

Unsurprisingly, holiday travel plummeted during the so-called “Golden Week” along with tourism spending, which fell to less than half of that in 2019, the last “normal” year.

And it’s not just one industry: Pessimism blankets other sectors, from automobile to real estate, as the world’s second-largest economy falters.

The Chinese economic slowdown poses a massive political challenge for Xi, whose party’s legitimacy in the past few decades has relied on rapid growth and rising incomes for 1.4 billion people. It’s also a harsh reality check for the international community: the world’s longtime growth engine is sputtering, just as the prospect of a global recession emerges.

But Xi’s costly “zero-Covid” intransigence is a natural outcome of the unprecedented amount of power he has amassed. For many Chinese officials, this policy is less about science and more about political loyalty to the country’s most powerful leader in decades.

Online videos abound of local health workers swabbing fruits, animals and even shoes for Covid testing despite the absence of sound scientific basis. China’s only Covid-related deaths in September were 27 people who were killed when their bus crashed on its way to a quarantine facility. Still, officials nationwide have doubled down on enforcing draconian rules, especially ahead of the party congress, helped by the world’s most sophisticated surveillance technologies.

China had boasted more security cameras than any other country even before Covid. Now, in the age of smartphones, mandatory apps allow the government to check people’s Covid status and track their movement in real time. Authorities can easily confine someone to their home by remotely switching the health app to code red – and they did just that on several occasions to stop potential protesters from taking to the streets.

Whether physical lockdowns or digital manipulation, these measures born out of “zero-Covid” have proven such effective means of control in a system obsessed with social stability that many worry Xi and his underlings will never ditch the policy.

A series of recent articles published by the party’s mouthpieces had reinforced such concern by stressing the policy’s “correctness” and “sustainability,” even before Xi hailed “zero-Covid” as a resounding success story in his two-hour speech Sunday. And state media fills its coverage with depictions of the “grim reality” in foreign countries where leaders supposedly turn a blind eye to mass fatalities and suffering caused by Covid – in contrast to China’s apparent triumph in saving lives with “minimal overall cost.”

For years, Xi’s cyber police have been fortifying the country’s so-called “Great Firewall” – perhaps the world’s most extensive internet filtering and censorship system that blocks and deletes anything deemed “harmful” by the party. Now supported by artificial intelligence, censors quickly scrub clean any posts seen as contradicting the party line – including on Covid.

This potent mix of propaganda and control under Xi appears to have had its desired effect on a large segment of Chinese society, creating a buffer for the leadership by convincing enough people of the superiority of China’s system even as millions of their fellow countrymen grow resentful of “zero-Covid.” But this approach, combined with prolonged border closure and escalating geopolitical tensions, also provides fertile ground for xenophobia.

The local child’s remarks on the Great Wall reflected that. But the true danger of the “blame the foreigners” sentiment comes when adults in powerful positions take advantage of it in the face of mounting pressure on the domestic front.

Since his ascent to the top in 2012, Xi’s ruling philosophy has become increasingly clear: Only he can make China great again by restoring the party’s – thus his – omnipresence and dominance, as well as the country’s rightful place on the global stage.

With China’s increasing economic and military might, coexistence with the West has given way to confrontation with the United States and its allies. Gone are the days of “hiding your strength and biding your time” – Chinese diplomats under Xi are proud warriors training fire on anyone who dares to question their government.

Underpinned by rising nationalism, China has started flexing military muscle beyond its shores. Tensions over Taiwan poses a real threat of war in Asia, as few doubt that “reunification” with the self-governed democratic island – long claimed by the Communist leadership despite having never ruled it – would be seen as the crown jewel of Xi’s legacy.

That outward power projection goes hand in hand with China’s sense of besiegement in a US-led world order, which Xi has made no secret of trying to reshape along with other autocrats like Russian President Vladmir Putin. Until that happens, though, the Chinese strongman’s instinct and demand for total control at home seems to have meant the erection of ever-higher barriers – in the real world and cyberspace – to keep out pesky outsiders, the perceived source of dangerous viruses and ideas.

A history paper released recently by a government-run research institute has gone viral as it, like Xi, upended a long-held consensus. Instead of denouncing the isolationist policy adopted by China’s last two imperial dynasties as a cause of their backward turn and eventual collapse, the authors defended its necessity to protect national sovereignty and security when faced with Western invaders.

The emperors of those dynasties, who also rebuilt parts of the Great Wall, failed to reverse their country’s decline back then. But the tools at their disposal were no match to the high-tech ones in the hands of China’s current ruler. Xi seems confident that his “walls” – among other things – will help him realize his oft-cited ultimate goal: the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

Whether or not he succeeds, the world will feel the impact for years to come.

Source link