[ad_1]

CNN

—

Jolie’s nerves were running high as she walked into the campus of Goldsmiths, the University of London, last Friday morning. She’d planned to arrive early enough that the campus would be deserted, but her fellow students were already beginning to filter in to start their day.

In the hallway of an academic building, Jolie, who’d worn a face mask to obscure her identity, waited for the right moment to reach into her bag for the source of her nervousness – several pieces of A4-size paper she had printed out in the small hours of the night.

Finally, when she made sure none of the students – especially those who, like Jolie, come from China – were watching, she quickly pasted one of them on a notice board.

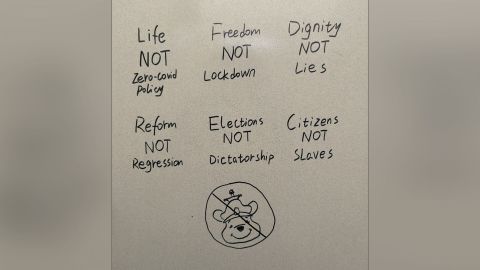

“Life not zero-Covid policy, freedom not martial-lawish lockdown, dignity not lies, reform not cultural revolution, votes not dictatorship, citizens not slaves,” it read, in English.

The day before, these words, in Chinese, had been handwritten in red paint on a banner hanging over a busy overpass thousands of miles away in Beijing, in a rare, bold protest against China’s top leader Xi Jinping.

Another banner on the Sitong Bridge denounced Xi as a “dictator” and “national traitor” and called for his removal – just days before a key Communist Party meeting at which he is set to secure a precedent-breaking third term.

Video shows rare protest in Beijing as Chinese leader is set to extend his reign

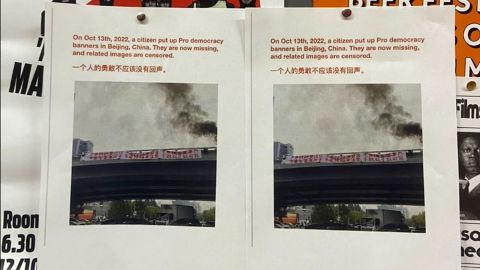

Both banners were swiftly removed by police and all mentions of the protest wiped from the Chinese internet. But the short-lived display of political defiance – which is almost unimaginable in Xi’s authoritarian surveillance state – has resonated far beyond the Chinese capital, sparking acts of solidarity from Chinese nationals inside China and across the globe.

Over the past week, as party elites gathered in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to extoll Xi and his policies at the 20th Party Congress, anti-Xi slogans echoing the Sitong Bridge banners have popped up in a growing number of Chinese cities and hundreds of universities worldwide.

In China, the slogans were scrawled on walls and doors in public bathrooms – one of the last places spared the watchful eyes of the country’s ubiquitous surveillance cameras.

Overseas, many anti-Xi posters were put up by Chinese students like Jolie, who have long learned to keep their critical political views to themselves due to a culture of fear. Under Xi, the party has ramped up surveillance and control of the Chinese diaspora, intimidating and harassing those who dare to speak out and threatening their families back home.

CNN spoke with two Chinese citizens who scribbled protest slogans in bathroom stalls and half a dozen overseas Chinese students who put up anti-Xi posters on their campuses. As with Jolie, CNN agreed to protect their identities with pseudonyms and anonymity due to the sensitivity of their actions.

Many said they were shocked and moved by the Sitong Bridge demonstration and felt compelled to show support for the lone protester, who has not been heard of since and is likely to face lifelong repercussions. He has come to be known as the “Bridge Man,” in a nod to the unidentified “Tank Man” who faced down a column of tanks on Beijing’s Avenue of Eternal Peace the day after the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989.

Few of them believe their political actions will lead to real changes on the ground. But with Xi emerging triumphant from the Party Congress with the potential for lifelong rule, the proliferation of anti-Xi slogans are a timely reminder that despite his relentless crushing of dissent, the powerful leader may always face undercurrents of resistance.

As China’s online censors went into overdrive last week to scrub out all discussions about the Sitong Bridge protest, some social media users shared an old Chinese saying: “A tiny spark can set the prairie ablaze.”

It would appear that the fire started by the “Bridge Man” has done just that, setting off an unprecedented show of dissent against Xi’s leadership and authoritarian rule among mainland Chinese nationals.

The Chinese government’s policies and actions have sparked outcries online and protests in the streets before. But in most cases, the anger has focused on local authorities and few have attacked Xi himself so directly or blatantly.

Critics of Xi have paid a heavy price. Two years ago, Ren Zhiqiang, a Chinese billionaire who criticized Xi’s handling of China’s initial Covid-19 outbreak and called the top leader a power-hungry “clown,” was jailed for 18 years on corruption charges.

But the risks of speaking out did not deter Raven Wu, a university senior in eastern China. Inspired by the “Bridge Man,” Wu left a message in English in a bathroom stall to share his call for freedom, dignity, reform, and democracy. Below the message, he drew a picture of Winnie the Pooh wearing a crown, with a “no” sign drawn over it. (Xi has been compared to the chubby cartoon bear by Chinese social media users.)

“I felt a long-lost sense of liberation when I was scribbling,” Wu said. “In this country of extreme cultural and political censorship, no political self-expression is allowed. I felt satisfied that for the first time in my life as a Chinese citizen, I did the right thing for the people.”

There was also the fear of being found out by the school – and the consequences, but he managed to push it aside. Wu, whose own political awakening came in high school when he heard about the Tiananmen Square massacre by chance, hoped his scribbles could cause a ripple of change – however small – among those who saw them.

He is deeply worried about China’s future. Over the past two years, “despairing news” has repeatedly shocked him, he said.

“Just like Xi’s nickname ‘the Accelerator-in-Chief,’ he is leading the country into the abyss … The most desperate thing is that through the [Party Congress], Xi Jinping will likely establish his status as the emperor and double down on his policies.”

Chen Qiang, a fresh graduate in southwestern China, shared that bleak outlook – the economy is faltering, and censorship is becoming ever more stringent, he said.

Chen had tried to share the Sitong Bridge protest on WeChat, China’s super app, but it kept getting censored. So he thought to himself: why don’t I write the slogans in nearby places to let more people know about him?

He found a public restroom and wrote the original Chinese version of the slogan on a toilet stall door. As he scrawled on, he was gripped by a paralyzing fear of being caught by the strict surveillance. But he forced himself to continue. “(The Beijing protester) had sacrificed his life or the freedom of the rest of his life to do what he did. I think we should also be obliged to do something that we can do,” he said.

Chen described himself as a patriot. “However I don’t love the (Communist) Party. I have feelings for China, but not the government.”

So far, the spread of the slogans appears limited.

A number of pro-democracy Instagram accounts run by anonymous Chinese nationals have been keeping track of the anti-Xi graffiti and posters. Citizensdailycn, an account with 32,000 followers, said it received around three dozen reports from mainland China, about half of which involved bathrooms. Northern_Square, with 42,000 followers, said it received eight reports of slogans in bathrooms, which users said were from cities including Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Wuhan.

The movement has been dubbed by some as the “Toilet Revolution” – in a jibe against Xi’s campaign to improve the sanitary conditions at public restrooms in China, and a nod to the location of much of the anti-Xi messaging.

Wu, the student in Eastern China, applauded the term for its “ironic effect.” But he said it also offers an inspiration. “Even in a cramped space like the toilet, as long as you have a revolutionary heart, you can make your own contribution,” he said.

For Chen, the term is a stark reminder of the highly limited space of free expression in China.

“Due to censorship and surveillance, people can only express political opinions by writing slogans in places like toilets. It is sad that we have been oppressed to this extent,” Chen said.

For many overseas Chinese students, including Jolie, it is their first time to have taken political action, driven by a mixture of awe and guilt toward the “Bridge Man” and a sense of duty to show solidarity.

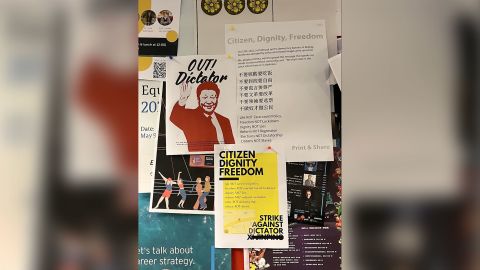

Among the posters on the notice boards of Goldsmiths, the University of London, is one with a photo of the Sitong Bridge protest, which showed a plume of dark smoke billowing up from the bridge.

Above it, a Chinese sentence printed in red reads: “The courage of one person should not be without echo.”

Putting up protest posters “is the smallest thing, but the biggest I can do now – not because of my ability but because of my lack of courage,” Jolie said, pointing to her relative safety acting outside China’s borders.

Others expressed a similar sense of guilt. “I feel ashamed. If I were in Beijing now, I would never have the courage to do such a thing,” said Yvonne Li, who graduated from Erasmus University Rotterdam in the Netherlands last year.

Li and a friend put up a hundred posters on campus and in the city center, including around China Town.

“I really wanted to cry when I first saw the protest on Instagram. I felt politically depressed reading Chinese news everyday. I couldn’t see any hope. But when I saw this brave man, I realized there is still a glimmer of light,” she said.

The two Instagram accounts, Citizensdailycn and Northern_square, said they each received more than 1,000 submissions of anti-Xi posters from the Chinese diaspora. According to Citizensdailycn’s tally, the posters have been sighted at 320 universities across the world.

Teng Biao, a human rights lawyer and visiting professor at the University of Chicago, said he is struck by how fast the overseas opposition to Xi has gathered pace and how far it has spread.

When Xi scrapped presidential term limits in 2018, posters featuring the slogan “Not My President” and Xi’s face had surfaced in some universities outside China – but the scale paled in comparison, Teng noted.

“In the past, there were only sporadic protests by overseas Chinese dissidents. Voices from university campuses were predominantly supporting the Chinese government and leadership,” he said.

In recent years, as Xi stoked nationalism at home and pursued an assertive foreign policy abroad, an increasing number of overseas Chinese students have stepped forward to defend Beijing from any criticism or perceived slights – sometimes with the blessing of Chinese embassies.

There were protests when a university invited the Dalai Lama to be a guest speaker; rebukes for professors perceived to have “anti-China” content in their lectures; and clashes when other campus groups expressed support for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests.

But as the widespread anti-Xi posters have shown, the rising nationalistic sentiment is by no means representative of all Chinese students overseas. Most often, those who do not agree with the party and its policies simply choose to stay silent. For them, the stakes of openly criticizing Beijing are just too high. In past years, those who spoke out have faced harassment and intimidation, retaliation against family back home, and lengthy prison terms upon returning to China.

“Even liberal democracies are influenced by China’s long arm of repression. The Chinese government has a large amount of spies and informants, monitoring overseas Chinese through various United Front-linked organizations,” Teng said, referring to a party body responsible for influence and infiltration operations abroad.

Teng said Beijing has extended its grip on Chinese student bodies abroad to police the speech and actions of its nationals overseas – and to make sure the party line is observed even on foreign campuses.

“The fact that so many students are willing to take the risk shows how widespread the anger is over Xi’s decade of moving backward.”

Most students CNN spoke with said they were worried about being spotted with the posters by Beijing’s supporters, who they fear could expose them on Chinese social media or report them to the embassies.

“We were scared and kept looking around. I found it absurd at the time and reflected briefly upon it – what we were doing is completely legal here (in the Netherlands), but we were still afraid of being seen by other Chinese students,” said Li, the recent graduate in Rotterdam.

The fear of being betrayed by peers has weighed heavily on Jolie, the student in London, in particular while growing up in China with views that differed from the party line. “I was feeling really lonely,” she said. “The horrible (thing) is that your friends and classmates may report you.”

But as she showed solidarity for the “Bridge Man,” she also found solidarity in others who did the same. In the day following the protest in Beijing, Jolie saw on Instagram an outpouring of photos showing protest posters from all over the world.

“I was so moved and also a little bit shocked that (I) have many friends, although I don’t know them, and I felt a very strong emotion,” she said. “I just thought – my friends, how can I contact you, how can I find you, how can we recognize each other?”

Sometimes, all it takes is a knowing smile from a fellow Chinese student – or a new protest poster that crops up on the same notice board – to make the students feel reassured.

“It’s important to tell each other that we’re not alone,” said a Chinese student at McGill University in Quebec.

“(After) I first hung the posters, I went back to see if they were still there and I would see another small poster hung by someone else and I just feel really safe and comforted.”

“I feel like it is my responsibility to do this,” they said. If they didn’t do anything, “it’s just going to be over, and I just don’t want it to be over so quickly without any consequences.”

In China, the party will also be watching closely for any consequences. Having tightened its grip on all aspects of life, launched a sweeping crackdown on dissent, wiped out much of civil society and built a high-tech surveillance state, the party’s hold on power appears firmer than ever.

But the extensive censorship around the Sitong Bridge protest also betrays its paranoia.

“Maybe (the bridge protester) is the only one with such courage and willingness to sacrifice, but there may be millions of other Chinese people who share his views,” said Matt, a Chinese student at Columbia University in New York.

“He let me realize that there are still such people in China, and I want others to know that, too. Not everyone is brainwashed. (We’re) still a nation with ideals and hopes.”

Artist wears 27 hazmat suits to protest China’s policies

Source link